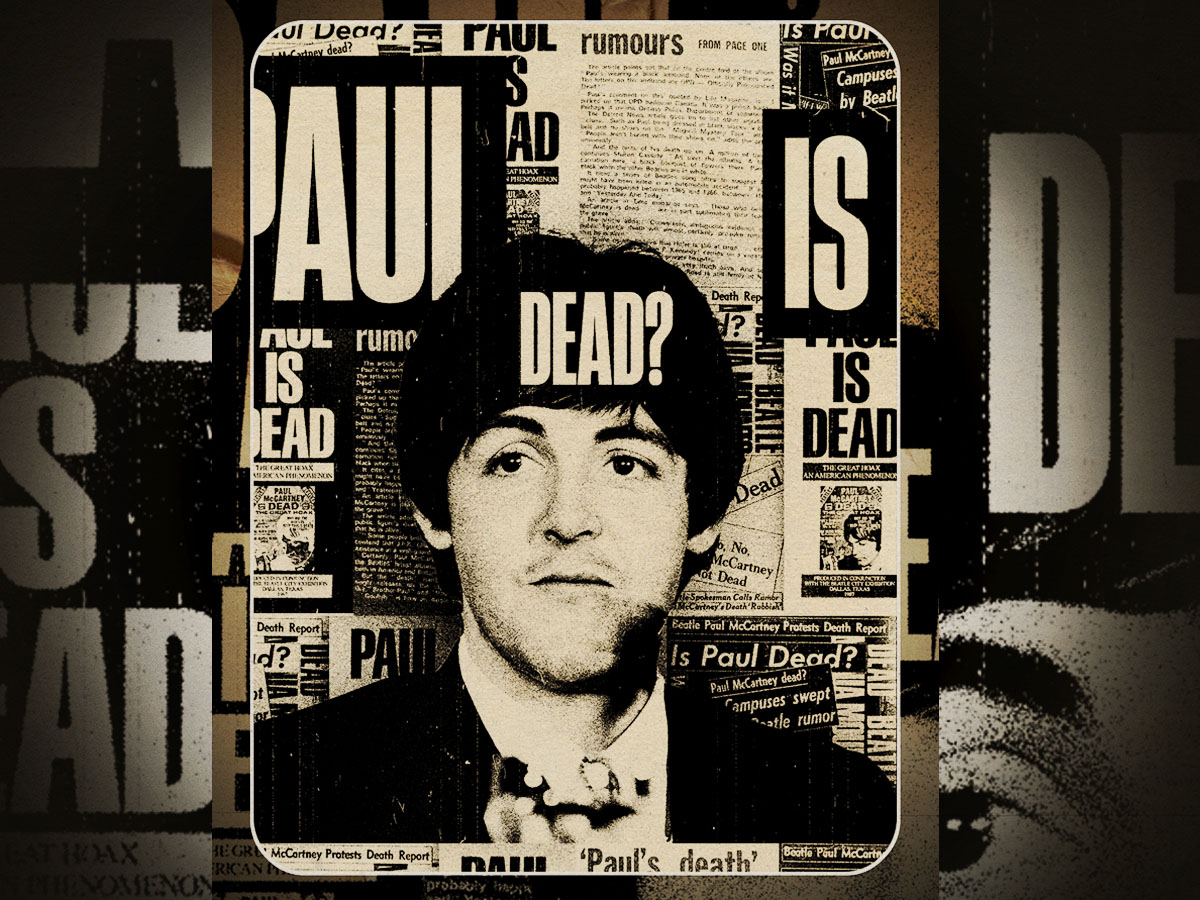

“I am alive and well and concerned about the rumours of my death. But if I were dead, I would be the last to know.” – Paul McCartney

Before we dive into the multitude of mythology and musically warped intrigue, let us first simply put: Paul McCartney is not dead. The Beatles legend has been the subject of near-constant headlines and unbridled scrutiny since he and the band burst into the collective consciousness in the earliest embers of the fiery 1960s. Things kicked into overdrive a little later in the decade.

Ever since 1967, rumours of Macca’s death have been greatly exaggerated, and the singer has had to deal with a continuous fascination with the conspiracy theory that The Beatles lost one of their principal songwriters during the band’s creative peak in a tragic car accident.

The theory goes that, instead of grieving and dealing with the loss of a band member, the band went into hiding for a couple of days, meditated on the prospect of life without their boy next door, and decided that the only way to move forward was to replace him. The winner of a Paul McCartney lookalike contest (which nobody can date), Mr William Campbell (who nobody can trace), was then hired to take Paul’s place forever. As you may agree, McCartney summed it up when he said, “It is all bloody stupid.”

The ludicrous facets of the charade have never stopped the curiosity, though, and there is a slight enjoyment in pawing through the remarkable set of improbable clues to come to the conclusion that is blinking at anybody who meets Sir Paul in the face. Ever since The Beatles became the global superstars they were by 1965, Beatlemania had meant that every column inch that could be devoted to the band was done so with prolific effect. It’s something we still see to this day.

The facts are that the Beatles were and still are big business, and conspiracy theorists around the world have pointed to this notion when surmising that the rumours are true, the clues are real, and Paul McCartney died on Wednesday, November 9th, 1966.

The ‘Paul McCartney is dead’ myth

The story goes that McCartney stormed out of a songwriting session with The Beatles, working on their album and, ironically, McCartney’s masterpiece, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and got into his Austin Healey car. Furious with the studio kerfuffle, he floored it, went off into the night in a fit of rage and was killed in a car crash, some even saying he was gruesomely scalped during the crash. A bit of blood and gore always has a habit of kicking the intrigue up a notch or two.

With the band floundering amid their pop peak, improbably, McCartney was then replaced by a lookalike called either William Shears Campbell (apparently referenced as Billy Shears on Sgt Pepper) or William Sheppard (supposedly referenced in ‘The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill’). Luckily, he was a man who could not only look like Macca, but sing like him, play a whole heap of instruments like him and write songs like him too – quite the find, and one that Simon Cowell would curse until his own dying day.

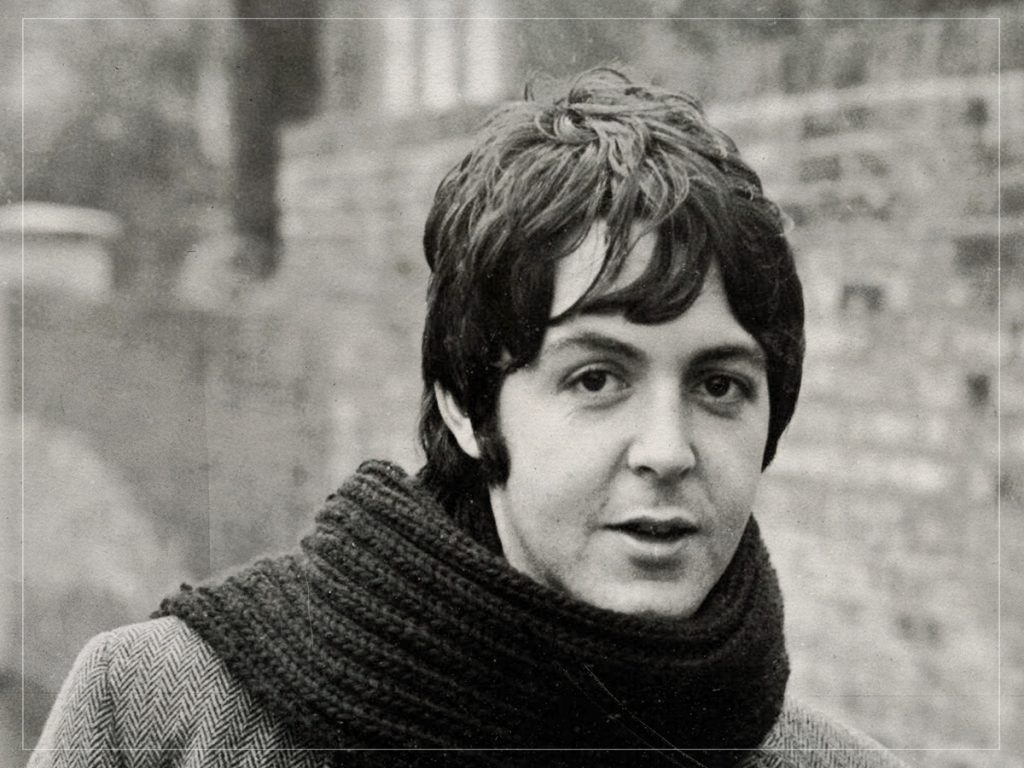

While McCartney was not in the country during this time, officially holidaying with then-girlfriend Jane Asher, there may have been some accidental muddling of facts that could have led to rumours starting to spread. McCartney was somewhat involved in two different car accidents, which bookend the proposed fatal incident. One saw the singer scar his lip, the reason why he grew a moustache in 1967, and the other involved his Mini Cooper, but he wasn’t driving, and he certainly wasn’t killed.

It did, however, prompt a Beatles newsletter, run by fans, to deny claims that Macca had died, written under the title heading ‘FALSE RUMOURS’, it reads: “The 7th January was very icy, with dangerous conditions on the M1 motorway, linking London with the Midlands, and towards the end of the day, a rumour swept London that Paul McCartney had been killed in a car crash on the M1. But, of course, there was absolutely no truth in it at all, as the Beatles’ Press Officer found out when he telephoned Paul’s St John’s Wood home and was answered by Paul himself.”

The moment the myth began

You might think that the newsletter issued should be considered the kernel from which the mighty tree of his hefty rumour began, but you’d be wrong. It might have been the passing nutrients from which such a seed could gain its growing power, but the real implantation began two years later.

The first time the rumours of McCartney’s apparent death were given any real credibility in a public sphere was on September 17th, 1969, when Tim Harper wrote a piece referencing the rumour in the Times-Delphic, a campus newspaper for Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. Harper was quick to insist that the piece was purely for entertainment purposes and cited his source as a friend by the name of Dartanyan Brown. Brown himself was also more than happy to pass the buck along, later saying he had caught the word from a musician who had spent time on the West Coast.

The truth, therefore, was clearly already out there and being highly manipulated by a society that had very little ability to fact-check at source. If such a story came to you today, you would be able to dispel it with one, possibly two, clicks. But in 1969, things could grow unabated for some time.

Following this article, the rumour gained more traction, and it was given an even larger audience when a caller by the name of ‘Tom’ called into Russ Gibb, a radio DJ on WKNR-FM in Michigan and asked to discuss the rumours of McCartney’s death. He pointed Gibb toward a song called ‘Revolution 9’ and told him to play it backwards. “I shoulda brushed the kid off,” recalled Gibb, “He said ‘play the record backwards’ I said ‘what!’”

Backmasking certainly wasn’t a very regular occurrence at the time, and this instance would push a whole generation to check every album they ever bought for satanic messages hidden in the backwards playing of the LP. The notion was a strange one at the time, but Gibb dutifully played it backwards and heard the words “number nine, number nine” turn into something different: “When I spun it backwards it said, ‘turn me on dead man, turn me on dead man’. I freaked.”

One person tuning in was Fred LaBour, a writer for the Michigan Daily who turned the radio call into an article using both the ‘information’ given and using his own imagination, including the name William Campbell, the man who would supposedly replace McCartney: “I made the guy up,” LaBour happily admitted.

“It was originally going to be Glenn Campbell, with two Ns,” he continued, with a more obvious nod and wink to the mischief, “and then I said ‘that’s too close, nobody’ll buy that’. So I made it William Campbell.” The article ran under the headline ‘McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought To Light’ on October 14th, 1969, as an obvious joke—but it still stoked the rumour mill into overdrive.

Why did a joke become a conspiracy

So, how does a joke become a conspiracy? With every time the story was passed along, it was perhaps left unchecked just that little bit longer. The weight of the perhaps one in ten people who actually believed it grew with every hundred who were notified. Soon enough, the 100 in 1000 started to look like they were on to something. But it wasn’t just word of mouth that seemed to support this new, startling story; there was evidence, too. Apparently.

This is where most of the sensational content of this conspiracy theory is held—the clues. The idea is that while The Beatles were happy to cover up the death of their friend and bandmate to preserve the unstoppable success of the Fab Four, their conscience encouraged them to leave clues through their music. It has led to nearly every single song the band ever made from 1966 onwards being meticulously pawed over for clues. On top of that, as many people will tell you, if you’re looking for connections, more often than not, you will find some.

The number of clues that the band supposedly left behind would suggest that if the rumour were to be true, they weren’t very concerned with keeping it concealed as suggested. We’ll run through all of them.

The songs and the ‘clues’

Look, or rather, listen, for the clues and they were easy enough to find. The Beatles, by this point, had written hundreds of songs, and it seemed like all of their lyrics were now pointing to something tragic befalling their leading man.

In the music, there are the opening words of ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’ which state: “I was alone, I took a ride, I didn’t know what I would find there”. Next up, the line “he didn’t notice that the lights had changed” from ‘A Day in the Life’ and, on top of that, the opening line of ‘She’s Leaving Home’ which supposedly highlighted the moment of the accident, “Wednesday morning at 5 o’clock as the day begins”. Meanwhile, ‘Lady Madonna’ reflects on the suppression of the media with the line, “Wednesday morning papers didn’t come”.

The ‘clues’, as some conspiracy theorists call them, keep coming and at the end of their classic song ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, Lennon can be heard muttering the words “cranberry sauce”, which were interpreted as “I buried Paul”.

A few more notes came with the phrases ”bury my body” and “oh untimely death” which appeared at the end of ‘I Am The Walrus’, a snippet taken from a BBC production of King Lear, seemingly arriving completely randomly. The muttering continues, too. Near the end of their song ‘I’m So Tired’, Lennon is heard saying “monsieur, monsieur, monsieur, how about another one?” When the song was played backwards, it was quickly heard as the now-iconic line: “Paul is dead, man, miss him, miss him”.

Of course, on ‘Revolution 9’, there is the aforementioned phrase “turn me on, dead man,” when played backwards, but it also includes the sound of a car crash and explosion. Other lines from songs outside of The Beatles have also added to the conspiracy, with Ringo’s song ‘Don’t Pass Me By’ apparently referring to the accident as well. ”I’m sorry that I doubted you, I was so unfair/ You were in a car crash, and you lost your hair,” the lyrics state.

The songs, it would seem, had stopped becoming pop-focused hits or deep explorations of love and livelihood in the world the band lived in, but platforms to, despite agreeing to carry on with their new replacements and apparently without the replacements’ prior knowledge, inform fans that McCartney had died.